💻 nutrition something something

I've been poking around on a project related to groceries, nutrition and prices.

☙

"Food" is a mature industry. The OG industry.

We can support a global population of billions, and it takes less and less of our time and resources to do it*. All while offering an ever increasing amount of choice.

...and yet, malnutrition is still a problem: from over-consumption, mis-consumption, and under-consumption; affecting the power and the wealthy. We've been at this for thousands of years!

Most people don't know what "eating healthy" is (ie. nutritional literacy is low), and the scientists still disagree what "eating really healthy is" (ie. there are still a lot of important open questions).

Even ignoring financial costs, "eating healthy" takes a lot of time and effort (and perhaps more than it used to in "simpler times").

Part of the issue is that consumers are fighting a battle they don't realize they're participating in. Food is a mature industry, with it's own interests, and it's had a long time to optimize how it interacts with consumers.

Contemporary consumers are offered a mind-boggling amount of choice. Walking into a modern supermarket presents a continuous torrent of information. I dare say that consumers are purposefully dazzled into a stupor. Each product viciously competing for your attention and your wallet.

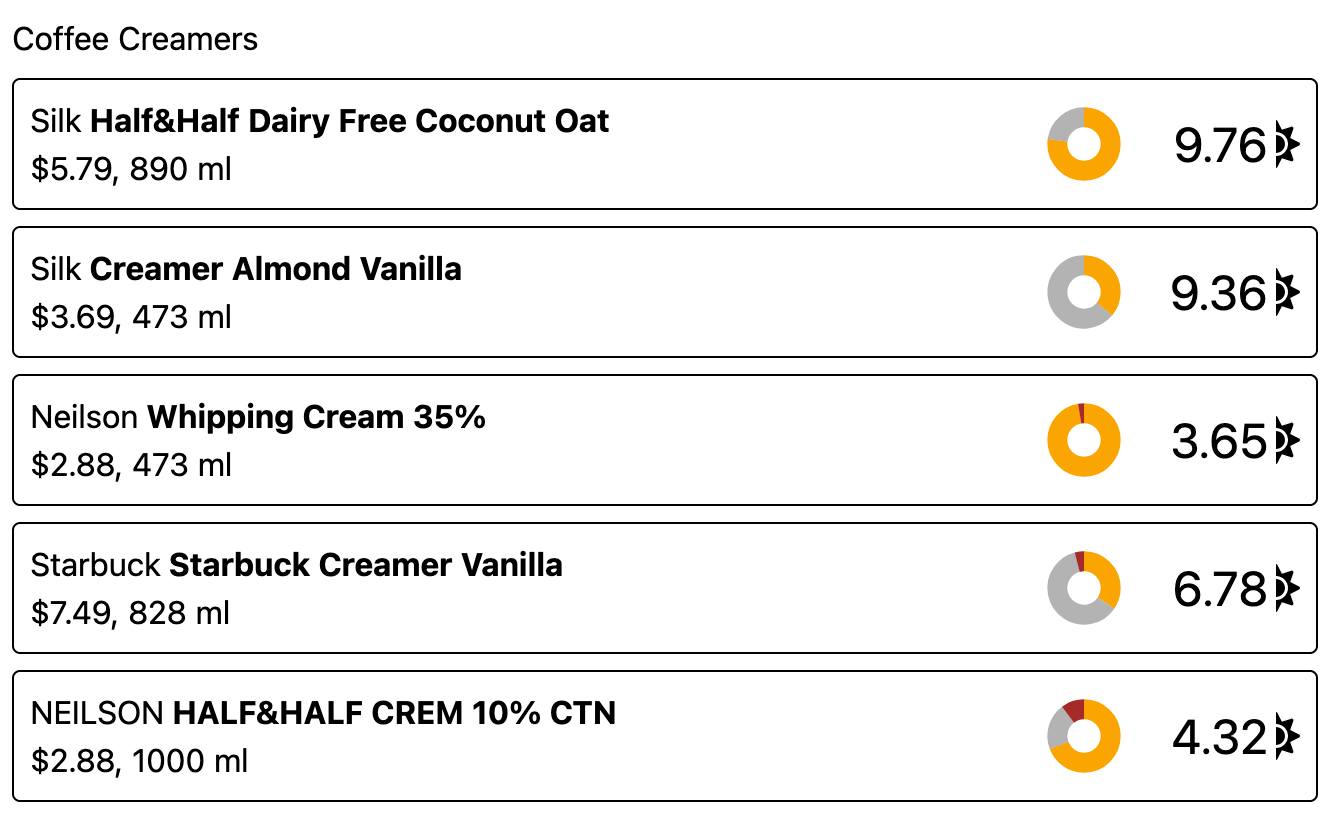

...and with all this information, I find myself standing in the dairy section, asking: "What should I be putting in my coffee? Is this almond-milk-half-and-half "healthier" than this full-fat-milk-based-creamer? Which is more nutritious? Which one is actually more expensive?" (Repeat every few metres).

Not to mention the bigger question: "what's a meal plan for an entire day of meals that is reasonably healthy and cheap?" Never mind, these hot-pockets sure look good.

"Eating healthy" takes a lot of effort and time: learning about nutrition, planning meals, comparing prices (which feeds back into planning meals), checking what you already have, doing the actual shopping, transporting, putting groceries away, cooking, cleaning. ...oh, and yes, the "eating" step.

...or, if you don't make the effort, you can just: hope someone else does it for you, pay a premium (say, to not price compare), or end up eating "unhealthily" for years (overeat, under-eat, miss out on nutrients).

☙

With all that said, the "thematic goal" of this "project" is: help people eat healthier for cheaper.

And right now, I'm exploring this problem in 3 parts:

- "wikigrocery" - a price comparison tool for groceries (camelcamelcamel for food)

- "bougie scoring" - a value to quickly compare products on price and nutrition ("$/g" is useless)

- "healthy frugal optimizer" - a program that calculates cheapest way to meet all nutritional requirements in a given area (the results will surprise you!)

A Way to Compare Prices of Groceries Over Time and Place

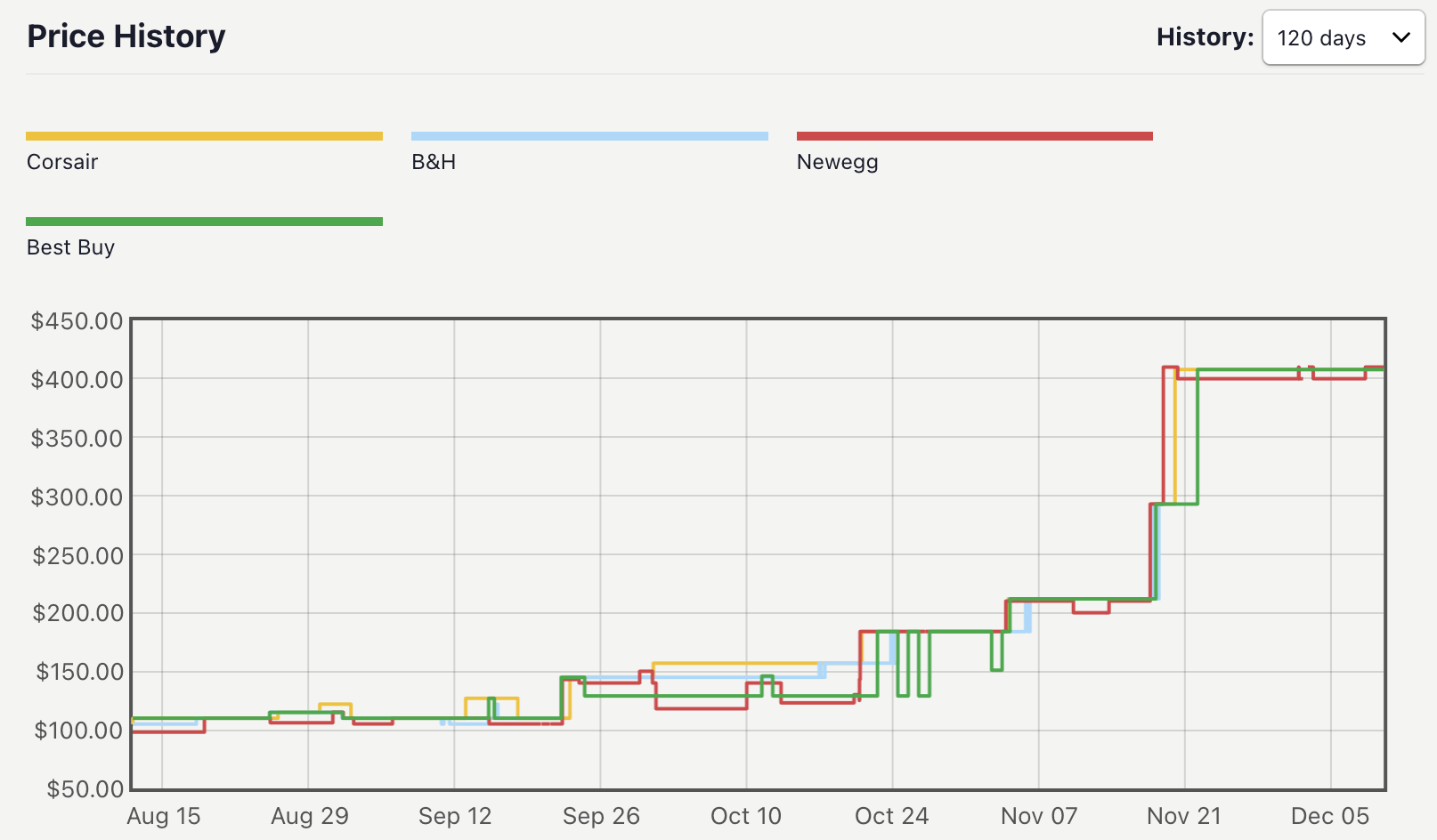

If I need to buy a computer part (say, some RAM) PCPartPicker shows me alternatives, prices at different stores, and a history of those prices:

I want that for groceries.

Standing in the grocery store, I want to know: "is this tofu pack worth it?"

- ...no, the other tofu pack is better value

- ...no, it's on sale frequently, wait a few days if you can

- ...no, it's 15% cheaper across the street

Part of the catch is that individual groceries are relatively cheap (unlike RAM), but bought regularly. Is it really worth the effort to shave $1 off your bag of milk? This time, probably not. But regularly? Yes (...if it was convenient enough to do so). How much effort time/effort would you be willing to spend to save 20% off your yearly grocery expenses? For many people "comparison shopping" is already worth it and they do it manually (they are money poor and/or time rich), but for many, it would only be relevant it was super convenient or offer something more.

The other catch is, that, until recently, the data was very hard to get.

Some thoughts on how to get the data....

- internet scraping

- COVID helped push pretty much all major supermarkets online

- crowdsourcing

- in-store capturing

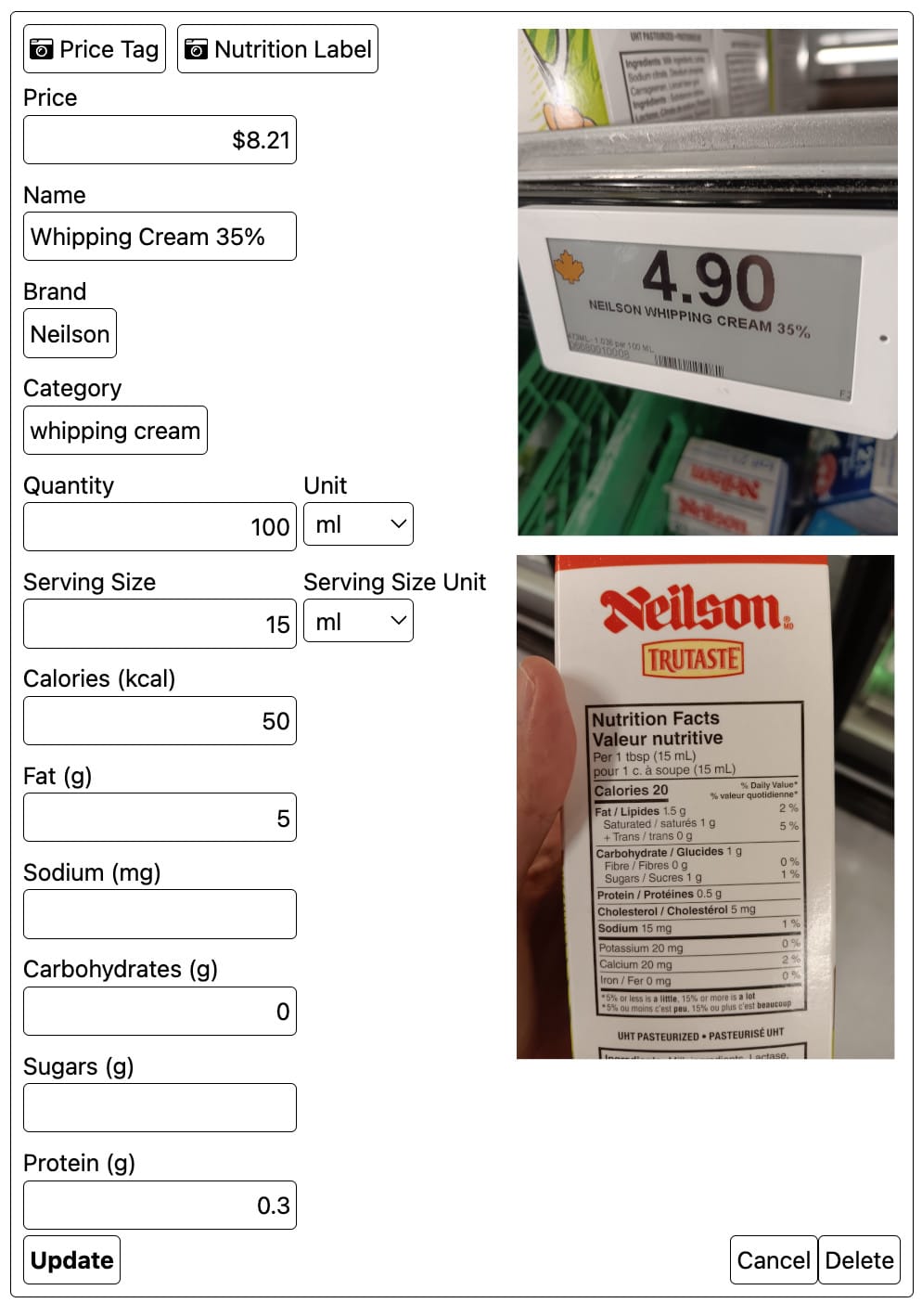

- have volunteers manually enter prices, or make it easy to take a photo (new digital price tags make this much easier)

- (for a while, I was doing this myself, and it's pretty tractable; at least for the range of products that one buys for themself)

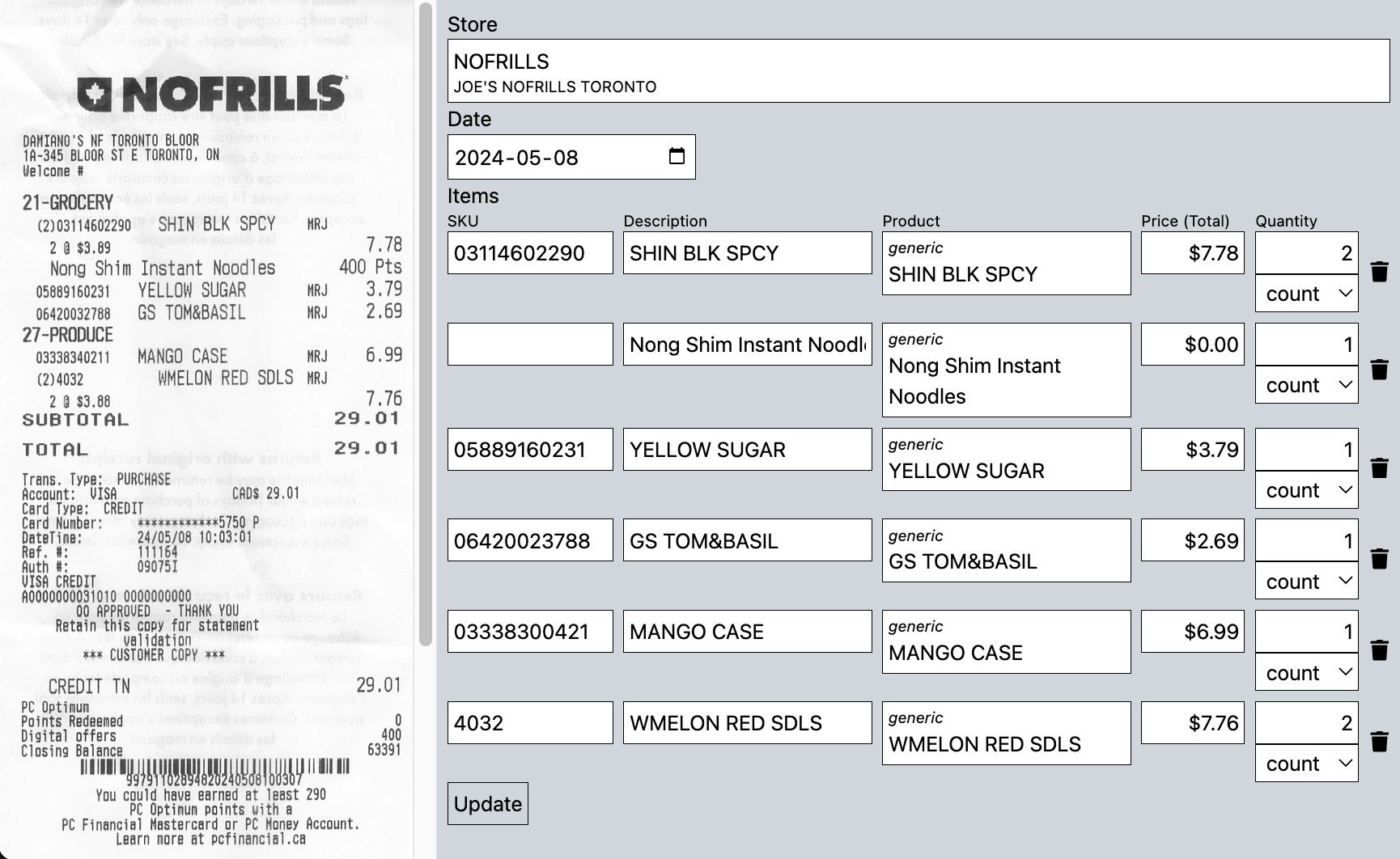

- receipt scanning

- Checkout51 and may other apps used to pay you to send in your receipts; now with LLMs, parsing them is relatively trivial (you just have to map each store's labels to actual products)

- in-store capturing

- flyer scraping

- Flipp has prices on the web, and if its on the web, it's possible to scrape (but this is just "advertised deals"... I want everything)

- direct partnerships

- every store has their prices in some software system (they now use them to update digital price tags); would they ever be incentivized to publish their prices on a price comparison site?

A bunch of hobbyists and some startups have started to do this:

- https://grocerytracker.ca

- https://www.sakisv.net/2024/08/tracking-supermarket-prices-playwright/

- https://www.eezly.com/

To do this at proper scale isn't trivial. There are 7,000 to 15,000 grocery stores in Canada (depending on what you count as a store), so about 3 to 4 million globally. With billions of products. And frequently changing prices.

On my end, I've been...

- experimenting with manual entry (spreadsheets, airtable)

- experimenting with receipt scanning (promising!)

- experimenting with AI aided photo capture from stores (promising!)

- (above resulted in coming up with a decent data model to capture all the information)

- experimenting with first steps on how to display the information

- planning to experiment with scraping from the stores I care about

The future of grocery shopping is likely to shift more and more towards online ordering and delivery (we saw this happen during COVID and it's remained popular in hyper-urban places like Hong Kong). If that comes to be, supermarkets will lose much of their "closest store to you" monopoly, and will need to compete on price more or find other ways to benefit consumers.

And then there's AI agents. If the future involves buying groceries at all, then you will likely delegate your food decisions to an agent - finally, an entity that will have the knowledge of nutrition, all prices, and the "patience" to optimize every penny for you. Such an agent would need access to the price information. So maybe, let's create the foundations for that digital marketplace?

A Way to Compare Apples and Oranges

...that is: "A Way to Compare Groceries on Price and Nutrition."

I find myself asking questions like:

- is frozen spinach much cheaper than fresh?

- what creamer-like alternative should I put in my coffee?

- which protein powder is a better deal?

- how much do you save by baking your own bread?

- cottage cheese vs greek yogurt?

I have a rough idea that I should aim for a certain number of calories, keep my carbs low, and get enough protein... and fibre of course. But are certain sources gonna break the bank a lot more than others? Going by the labels at the store, I can't tell (...without pulling out a calculator at least).

☙

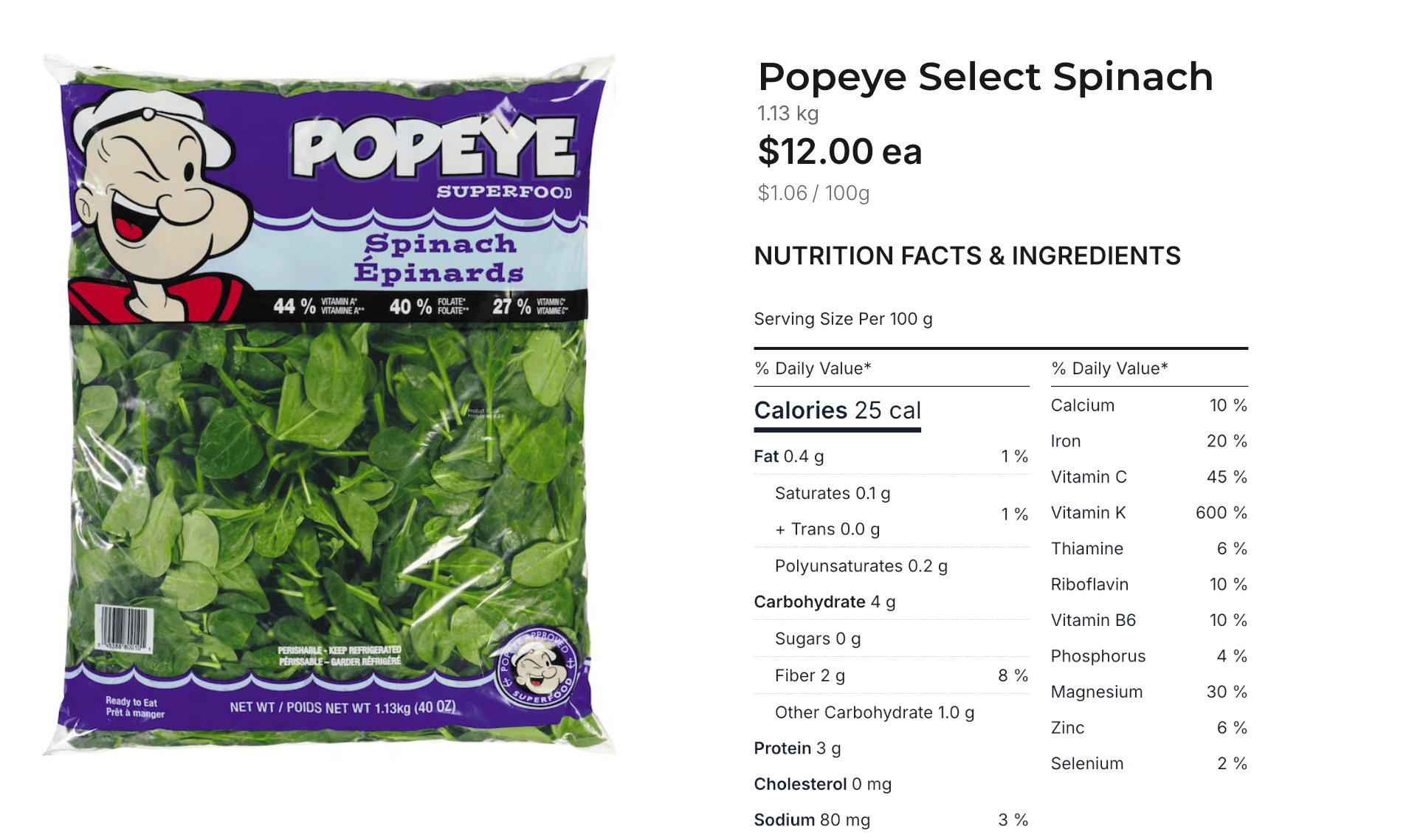

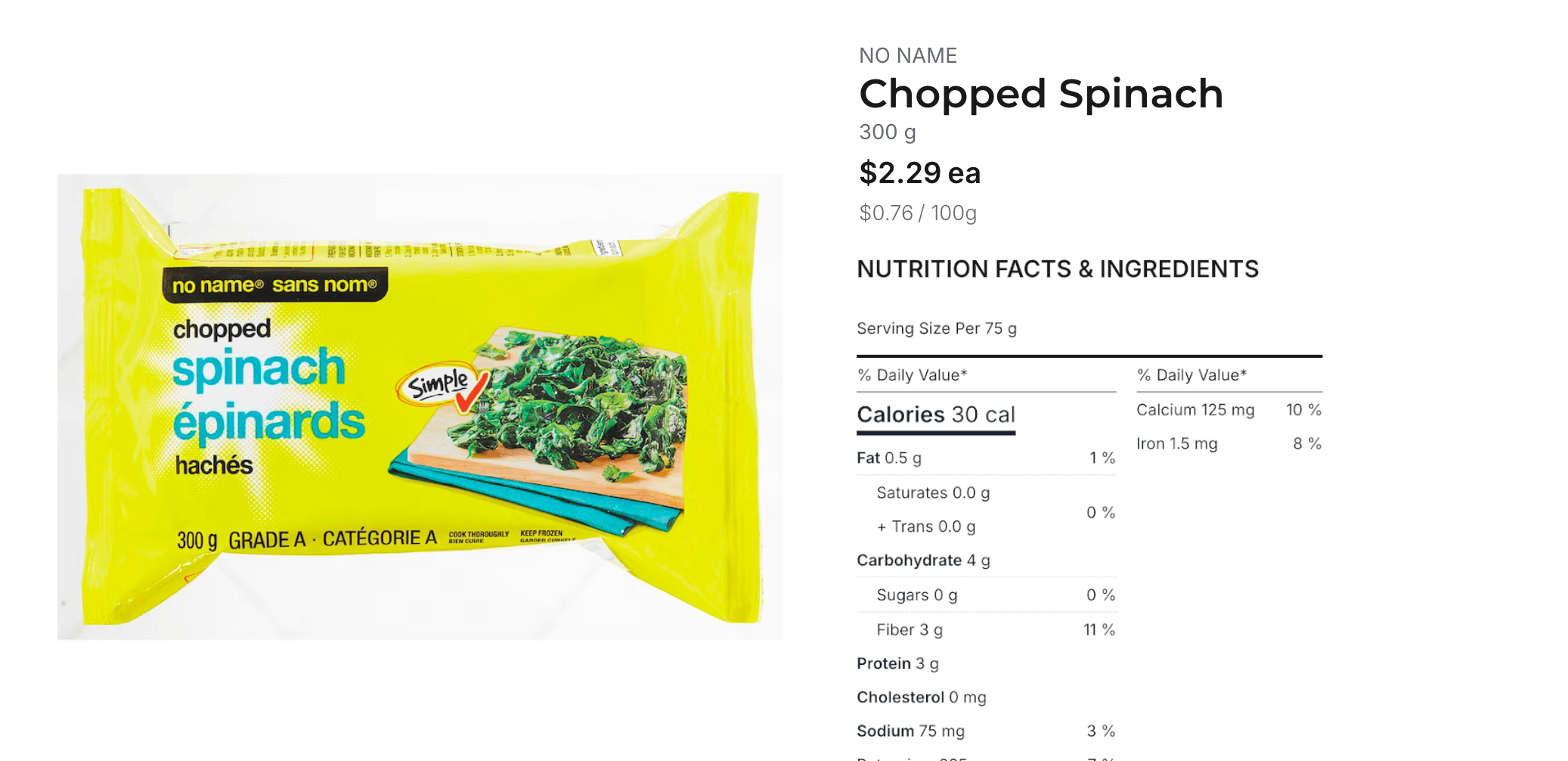

Quick, you're making a quiche - how much cheaper do you think frozen spinach is vs fresh?

If we go by the given $/g breakdowns.... 0.76/1.06 = 0.716, so frozen is 0.7x of fresh (ie. 30% cheaper).

But is that the whole story?

What if we look at the calories:

fresh spinach: $12.00/ 1.13kg * 100 g / 25 cal => $4.24 / 100 cal

frozen spinach: $2.29 / 300g * 75 g / 30 cal => $1.91 / 100 cal

Now, frozen is 0.45x of fresh. What's going on?

It's water: frozen spinach has more spinach per gram than fresh spinach.

("Spinach per gram of spinach" was not on my bingo card for the year, but here we are).

Will I still buy fresh? Only if I want a salad.

☙

How about a trickier question:

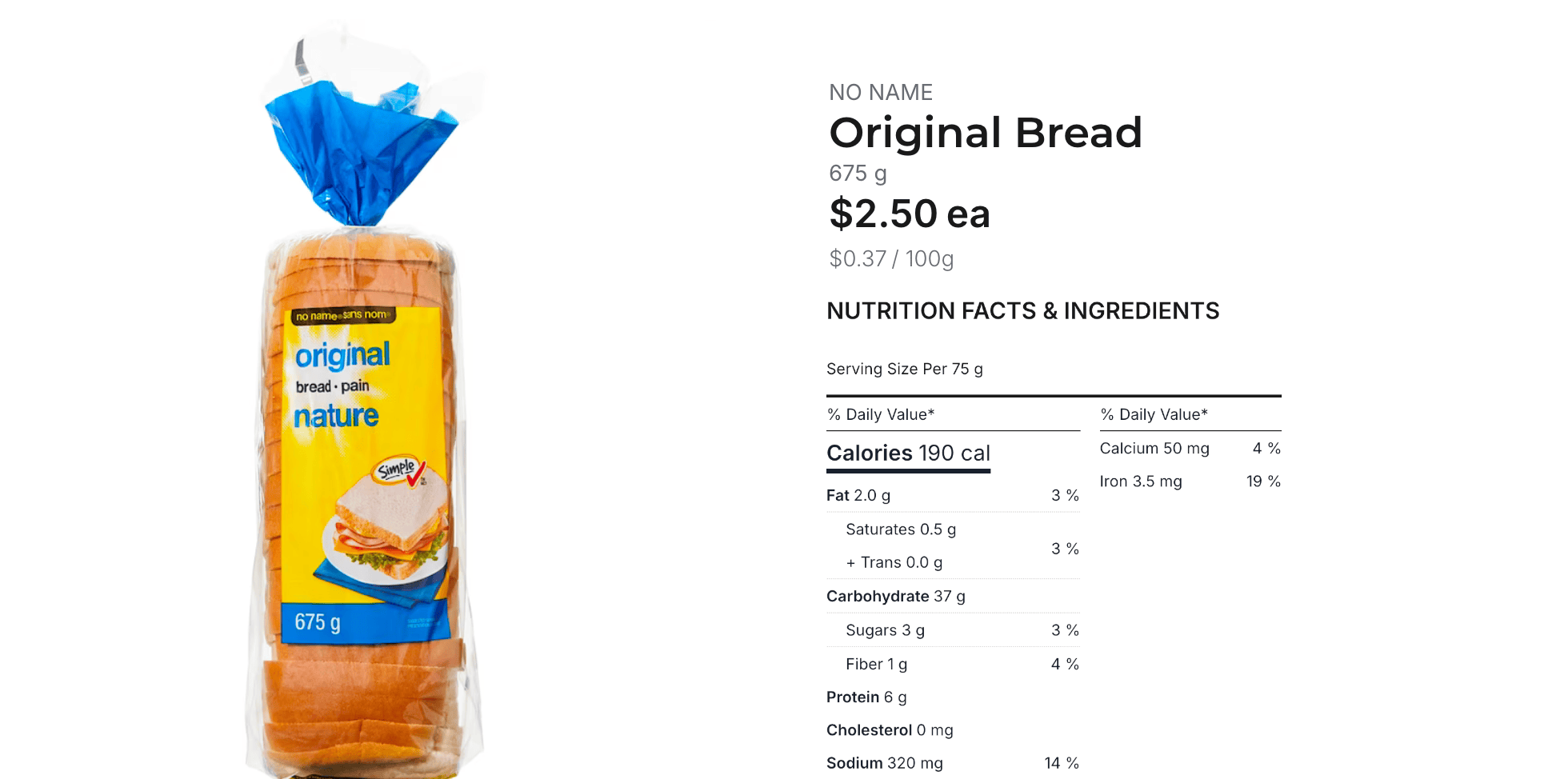

How much more expensive is quinoa than white bread?

Now we're into apples and oranges territory, so first, let's convince ourselves that the macros are at least similar:

Macros:

Quinoa:

Fat 2.5g * 9cal/g / 160cal => 14%

Carbs 29g * 4cal/g / 160cal => 72%

Protein 6g * 4cal/g / 160cal => 15%

Bread:

Fat 2g * 9cal/g / 190cal => 10%

Carbs 37g * 4cal/g / 190cal => 78%

Protein 6g * 4cal/g / 190cal => 12%

Carb heavy, but with a surprising amount of fat and protein. Given the wide variety of foods, these are very similar macros.

Onto the price comparison...

The $/g labels are completely useless to us. Let's take the $/calorie approach:

Quinoa: $7.49 / 907g * 45g / 160 cal => $0.232 / 100 cal

Bread: $2.50 / 675g * 75g / 190 cal => $0.146 / 100 cal

So bread is 0.63x of quinoa (ie. 40% cheaper, or, "quinoa is 1.6x the price of bread").

Will that stop me from buying quinoa? No. But damn, I am pretty impressed with bread.

☙

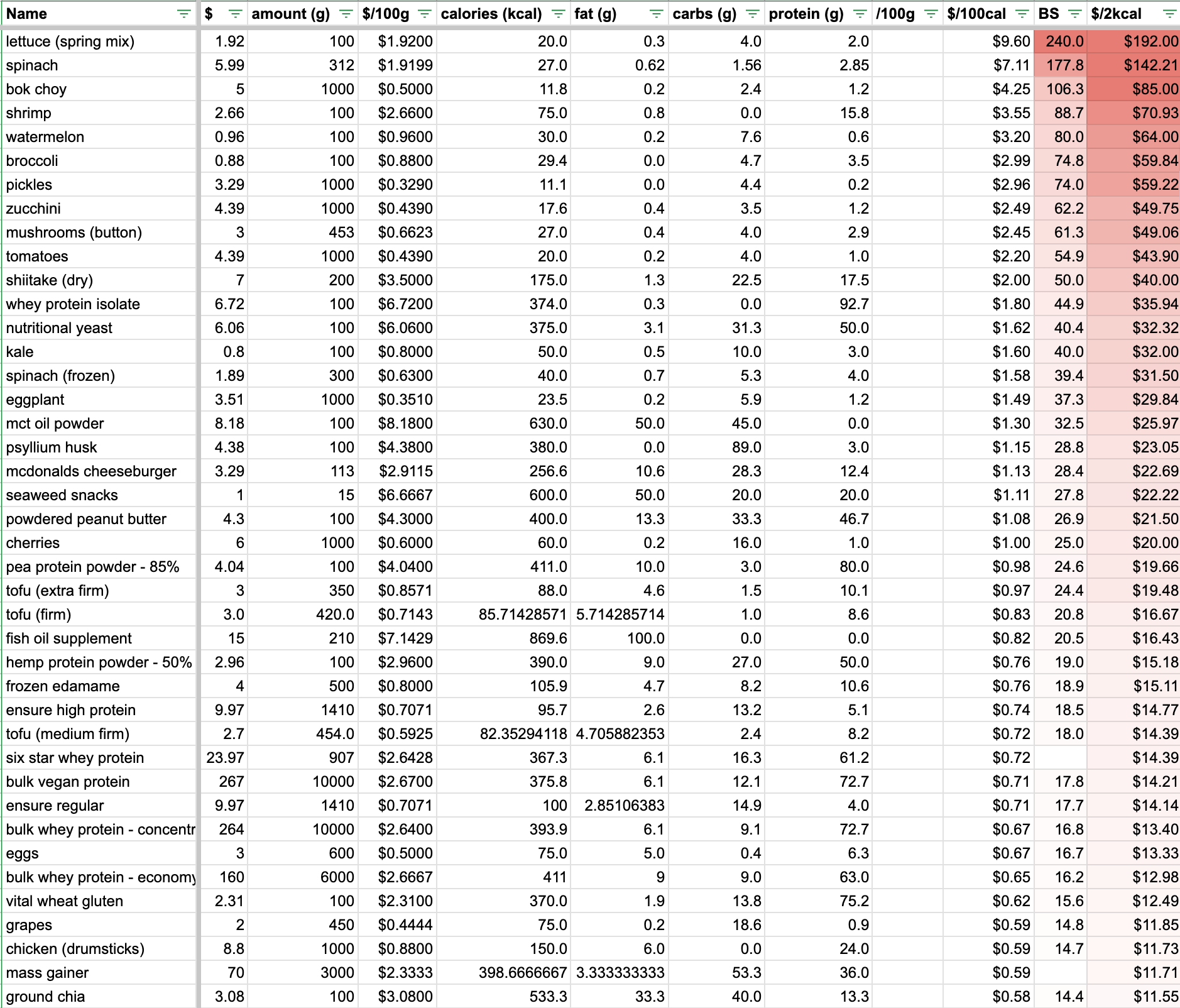

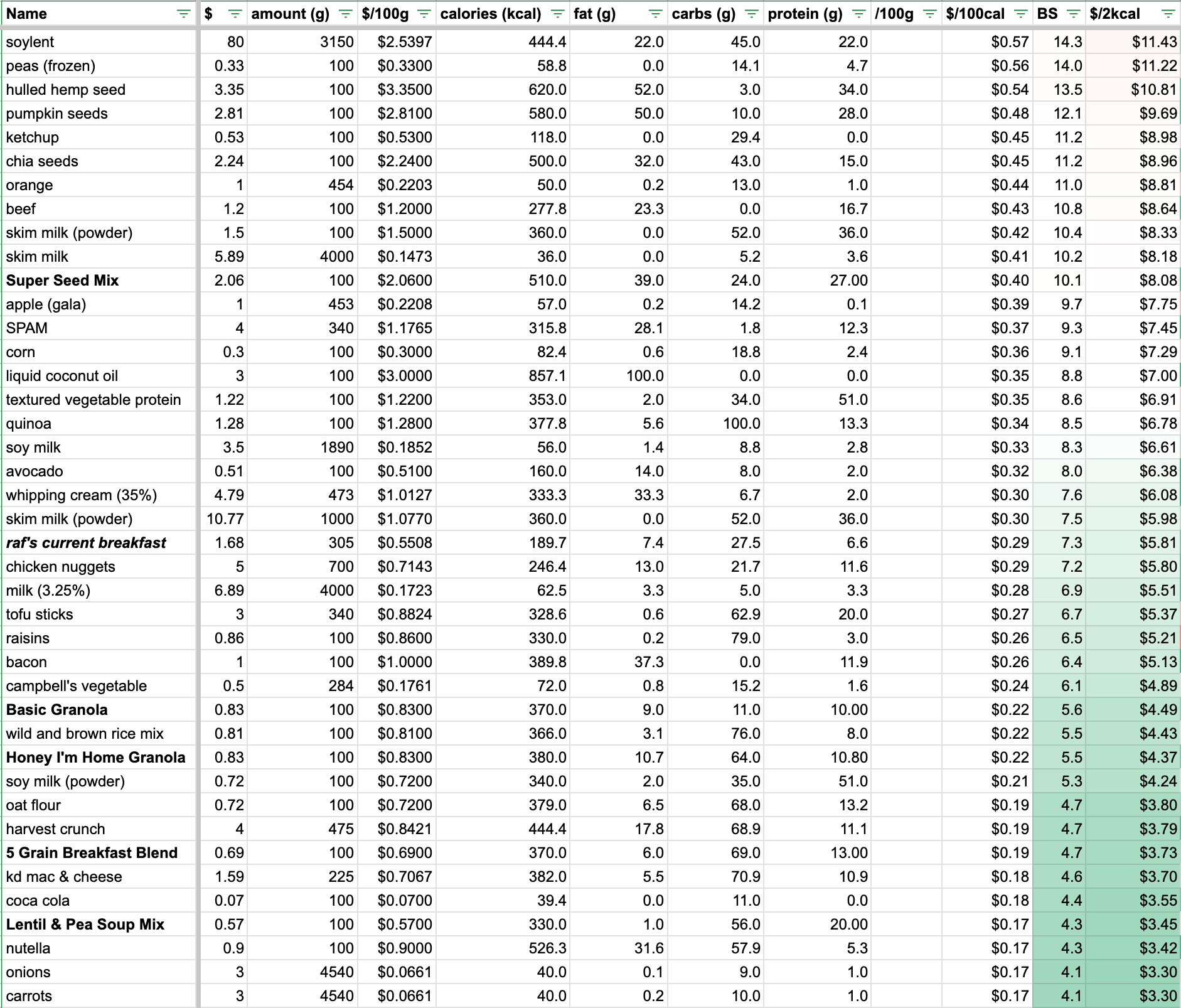

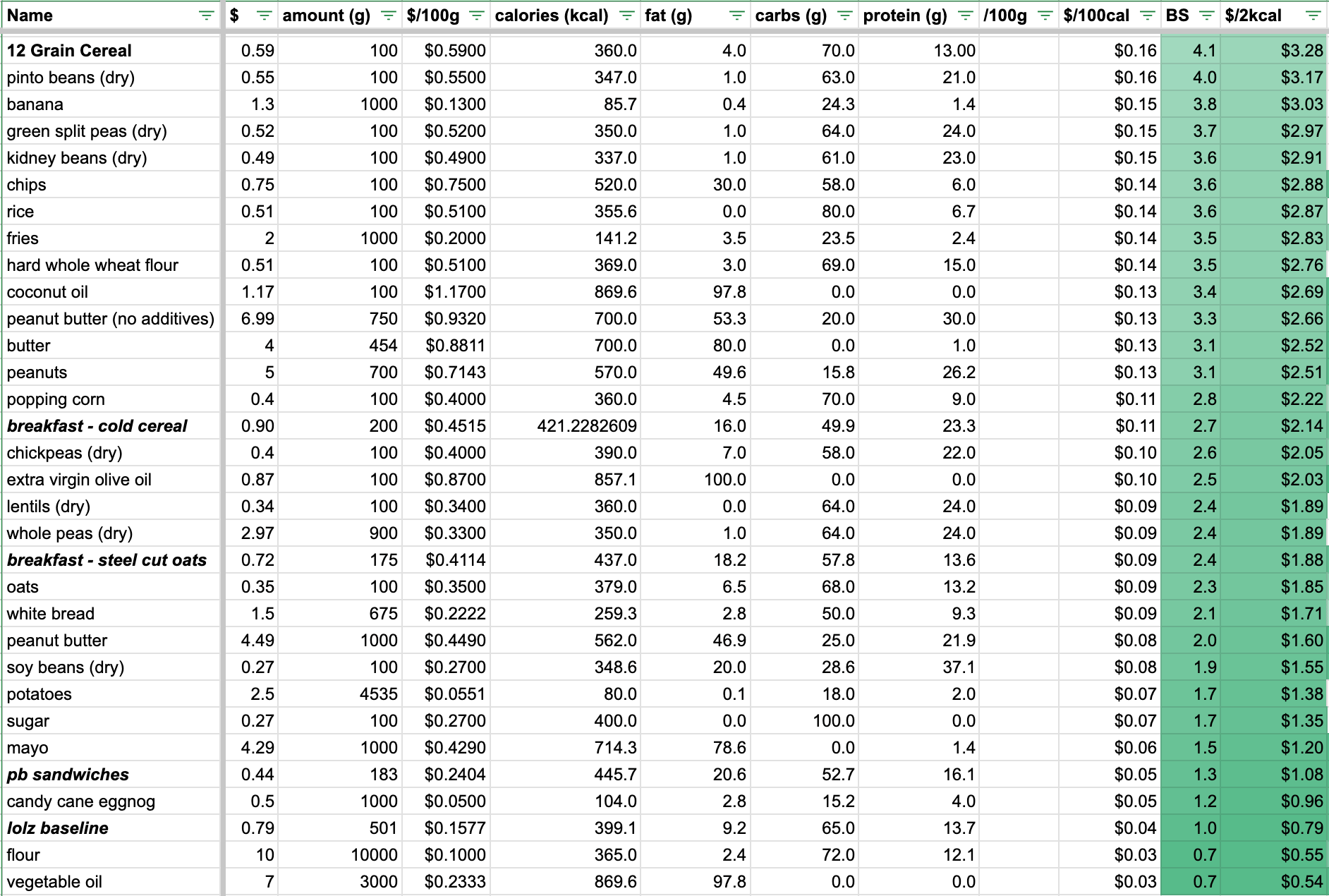

One chilly February morning, Canna and I took the $/calorie approach and applied it to a bunch of foods:

Can't give up an opportunity to make a good ol' spreadsheet!

Turns out flour and vegetable oil are very inexpensive (3 cents / 100 cal) - but I suspect not enough to live off of.

Home-made peanut butter sandwiches come in at 5 cents / 100 cal and seem closer to being a "forever meal" (unfortunately, the wheat + peanuts combination isn't "complete", so you don't get enough of the lysine protein).

In comparison, tomatoes, and watermelons, and mushrooms are more than 40x as expensive (calorically). They must be good for something, right? We'll come back to that.

☙

"$ per 100 calories" is a fine measure, but arbitrary.

To give us something easier to reason about, we divided it by $0.04 to get a ratio of "how much more expensive is some food than a baseline." Peanut butter sandwiches: 1.3x; tomatoes: 55x. We got to calling this the "bougie score." (Second to last column in the spreadsheet above)

An alternative (in the final column), is "$ / 2000 calories", which is just 20x of the "$ / 100 calories" measure, but suddenly relevant: 2000 calories is the "average" daily recommended value, so the "$ / 2000 calories" metric can be a proxy for "$ / day". Peanut butter sandwiches: $1.08 per day. Soylent: $11.43 per day.

Going back to the challenges from before:

- fresh spinach: $85 / day

- frozen spinach: $38 / day

- quinoa: $4.64 / day

- white bread: $2.92 / day

I now like to call spinach "calorically void".

Why does my doctor keep pushing "leafy greens"?

Is "big leaf" at it again?

(No: it's vitamins, fibre and folates).

So, "$ / 2kcal" is not perfect - it still fails at comparing different macros, and completely skips on fibre and micronutrients - but it is at least somewhat useful, and I wish it were reported instead of "$/gram".

In my app prototype, I've been using $/2kcal to compare against products in a similar group (and show a mini-visualization of the macro-nutrient breakdown):

But can we do better?

Optimizing for Price and Nutrition

When describing the "bougie score" above, I mentioned comparing foods to a "baseline meal". But what baseline? Perhaps: the theoretical cheapest combination of foods that would meet all nutritional requirements (macro and micro, minimums and maximums).

When you dig into it, nutritional guidelines include minimums and maximums for:

- total caloric intake

- macros

- protein, carbohydrates, fat

- fibre

- omega-6 and omega-3

- fibre

- micros

- vitamins (A, D, E, K, C, thiamin, riboflavin

, niacin, B6, folate, B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, choline)

, niacin, B6, folate, B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, choline) - elements (arsenic, boron, calcium, chromium, copper, fluoride, iodine, iron, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, phosphorus, selenium, silicon, vanadium, zinc, potassium, sodium, chloride, sulfate)

- vitamins (A, D, E, K, C, thiamin, riboflavin

Every one of these requirements exists because we figured out the hard way that the underlying nutrient hurts someone if they consume not enough of it and/or too much of it. (In fact, each "vitamin" was discovered only because of the malady it caused: scurvy = Vitamin C; rickets = Vitamin D; beriberi = Vitamin B12, etc.)

According to the USDA, a lot of Americans struggle meeting all of these requirements. 89% get their recommended protein intake, but only 8% get their recommended fibre.

It is very possible that no one meets all the requirements.

...because it is a legitimately hard problem!

Let me rephrase the "feeding yourself problem" more "technically":

- you have the choice of combining from 1000+ different foods, each with different macro and micro profiles

- you need to get between, say, 1900 and 2100 calories per day

- and you need to meet the minimums and maximums for 40 micronutrients

Oh, and in practice...

- the information isn't readily available in store

- foods expire

- foods take up space in your fridge and pantry

- the result needs to be palatable

- you have finite amounts of time and money (and most people want to spend very little of either on this problem)

It's actually a bit of a wonder that human cultures around the world roughly figured it out (ex. realizing that you need rice and beans to avoid malnutrition). But with modern engineered foods and supermarkets with misaligned interests, we may be taking some steps backward.

Back to the problem: it's near impossible for a person, but easy for a computer. Enter Integer Linear Programming. We can "feed" a database of foods (including prices and nutritional information) into a program, then write an algorithm to determine the quantity of each food such that our 40-ish constrains are met, while also minimizing price. (n my case, I used Clojure + OJAlgo.

Let's try it out. (Mind you, the following examples use prices from 2023 and a incomplete database of nutritional information. This is a WIP.)

☙

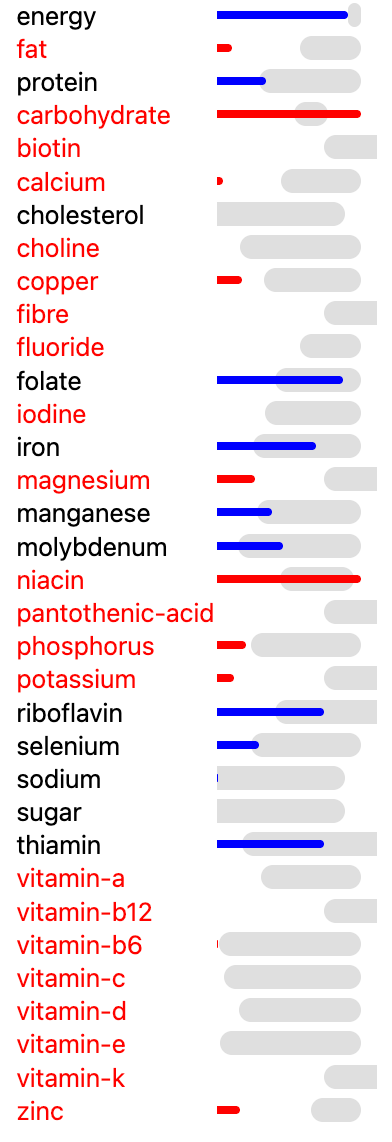

Let's start with just constraining calories:

Constraints:

Calories: 2000 - 2200

Result:

547g flour

Cost:

$0.55

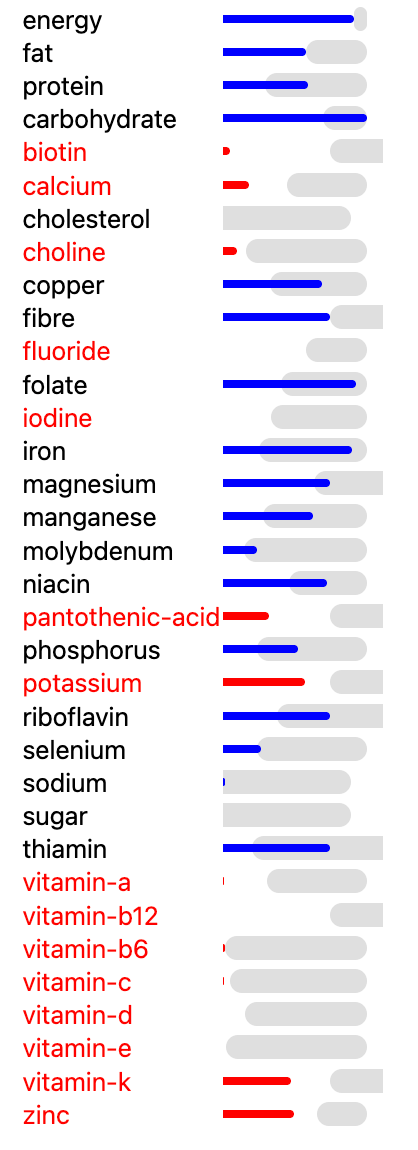

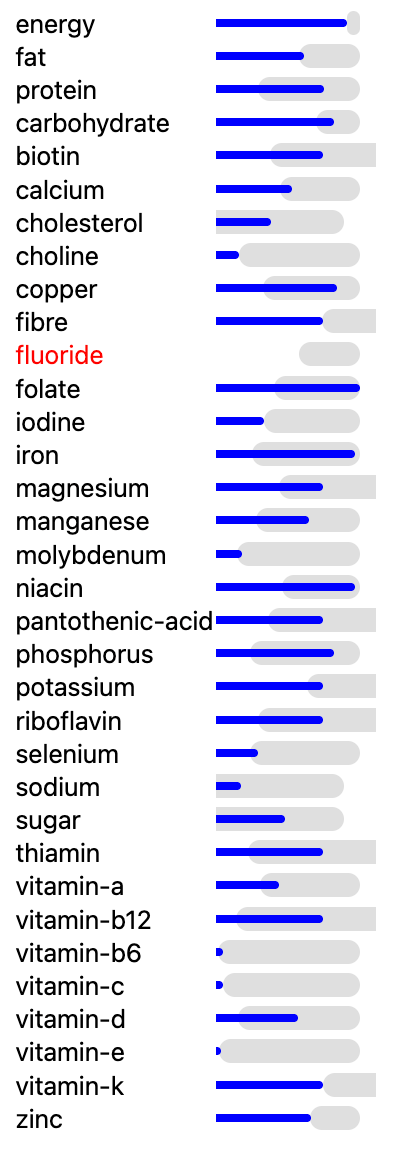

That's a lot of bread. ...and obviously not a "complete" diet:

Not enough fat. Too many carbs. Missing out on fibre and a lot of micronutrients.

(The below diagram evaluates the meal plan against all requirements, even though we ran it only for some)

☙

Let's add macros:

Constraints:

Calories: 2000 - 2200

Carbohydrates: 45% - 65%

Fat: 20% - 35%

Protein: 10% - 35%

Result:

413g flour

63g mayo

3g ensure high protein

1g peanut butter

1g soy beans (dry)

Cost:

$0.71

Slather that bread with some mayo!

...and apparently sneak in a tiny amount of other protein sources? (which are negligible in practice, but, optimizers be optimizin'). (Note to self: change the code to eliminate these scraps)

It's worth noticing that the price increased. Any time we add more constraints, we should expect the price to increase (or at best, stay the same); it will never decrease with more constraints (because as we add constraints, we're reducing the solution space; if there was a better solution, we would have found it with less constraints!)

Our bread-and-may is still not great on fibre and micro-nutrients (because we didn't ask the optimizer for any):

☙

Let's add fibre as a constraint:

Constraints:

Calories: 2000 - 2200

Carbohydrates: 45% - 65%

Fat: 20% - 35%

Protein: 10% - 35%

Fibre: 38g - ...

Result:

275g flour

122g soy beans (dry)

119g whole peas (dry)

11g vegetable oil

2g peanut butter

1g chickpeas (dry)

Cost:

$1.03

Mayo is out, and beans and peas are in. I knew I'd see beans eventually.

Micro-nutrients, vitamins in particular, are still lacking:

☙

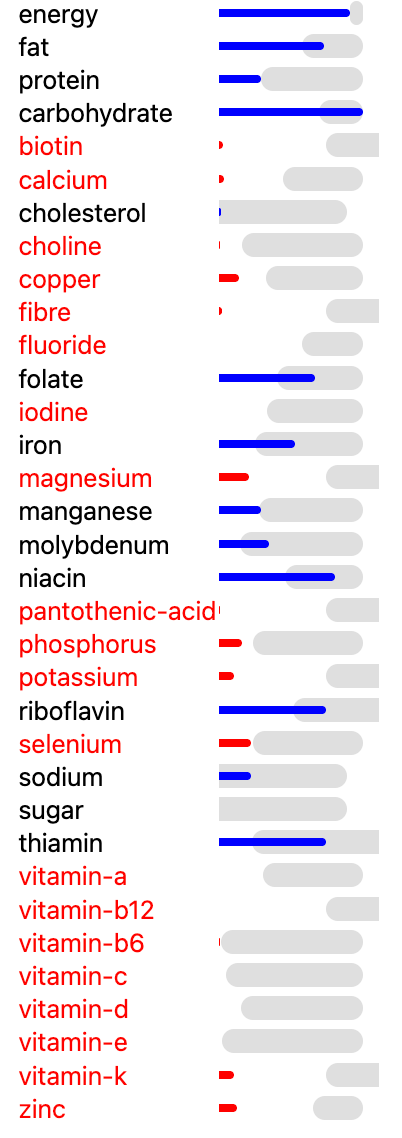

Let's add in constraints for those micro-nutrients:

Constraints:

Calories: 2000 - 2200

Carbohydrates: 45% - 65%

Fat: 20% - 35%

Protein: 10% - 35%

Fibre: 38g - ...

Biotin: 30µg - ...

Calcium: 1100mg - 2500mg

(and 27 others)

Result:

521g skim milk

190g soy beans (dry)

149g flour

92g whole peas (dry)

46g potatoes

27g eggs

4 vitafusion multivites gummies

3g frozen spinach

2g milk

1g ensure high protein

Cost:

$1.93

That's looking pretty "normal".

...and spinach, finally! It has purpose. (I suspect if I banned multi-vitamins, spinach would make a big comeback)

For less than $2 we met all the constraints - all* blue baby:

(*Ignore fluoride for now - it's in the graphic, but not in the food database)

☙

Caveat time!

This is a proof-of-concept. Please do not switch to eating the above meal every day!

First off, some "technical" issues:

- price information is old (2023)

- price information is just a few handpicked stores around me

- my food nutrition database is missing info

- which might mean we're going over the limit on some nutrients

- (and under on some, but that's less of a "danger")

- a bunch of nutritional constraints that exist in the guidelines were skipped (lack of nutritional data for the foods)

- the nutritional guidelines were picked for a middle-aged male with no dietary preferences

These can all be addressed, but what can't be addressed, is this big boy:

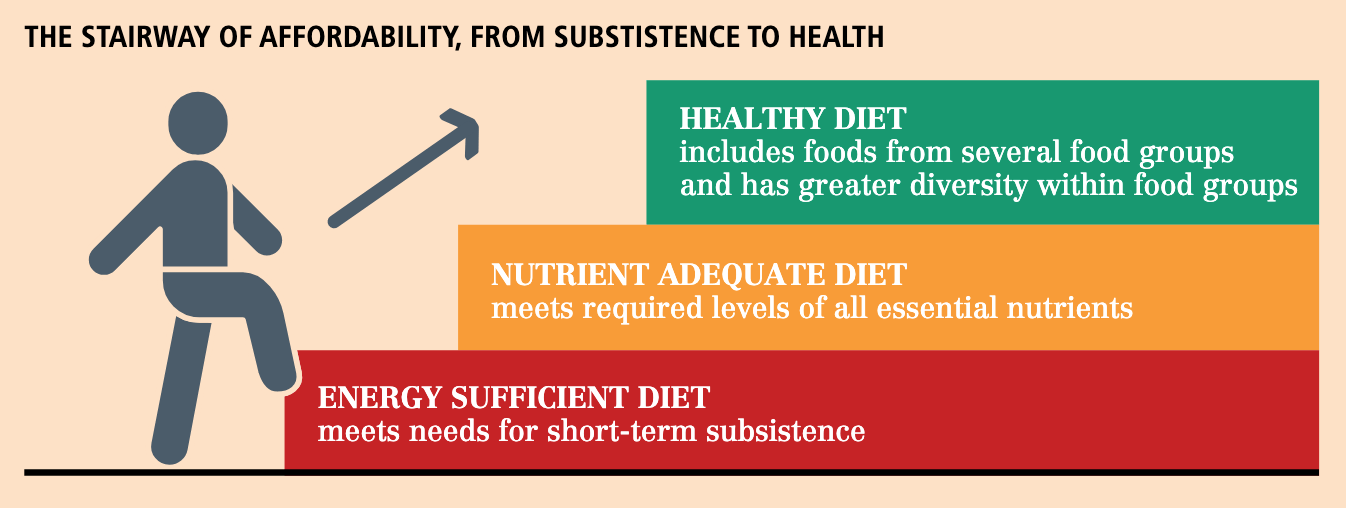

This whole approach reeks of "nutritionism," that is: believing that "nutrition science is complete, and fully captured by the Recommend Daily Intake values." But the truth is that we don't know what we don't know. It's dangerous to eat a very narrow selection of foods over a long period of time.

(Above image from this fantastic United Nations food security paper)

In their latest Food Guide, Health Canada recognized that a database of numbers isn't effective at changing people's purchasing habits, and shifted towards what I describe as more "holistic" guidelines:

- eat a variety of health foods each day

- have plenty of vegetables and fruits

- eat protein foods

- choose whole grain foods

- limit highly processed foods

- (particularly ones with added salt and sugar)

- make water your drink of choice

- (and others, it's a good read, I highly recommend)

That being said, helping people identify a set of meals that will meet nutritional requirements, even in a "nutritionist" way, may still be better for a lot of people than their status quo (when I started down this journey, I was way off on my macros and micros, and getting closer to the guidelines made me feel much better).

☙

Right, so, anyway... the cheap-meal calculator is a bonus; we started down this path of "the baseline meal" to calculate a score for all other foods.

Filling in the gaps mentioned above, we could probably find a new price, say, $2.50, and use that for our caloric baseline ($2.50 / 2000 calories => $0.125 / 100 calories).

The above spreadsheet used $0.04 / 100 calories, and could be updated. (Shrimp would go from 89 bougie to just 29.)

But that still won't solve the "vegetable oil - at a bougies score of 0.21 - looks like a great deal!" (notice how it doesn't show up at all in our final meal plan).

So we need something else...

☙

What if... when considering some food, we were to calculate how much more expensive it would make the "baseline meal" if we required 250 calories of that food.

Say, for, shrimp: force 250 calories of shrimp into a blank meal plan (with all of shrimp's nutritional characteristics), then force the algorithm to figure out how to make the rest of the meal plan work. Finally, see how much more expensive the "baseline+shrimp plan" is than the "baseline plan."

250 calories of vegetable oil, even though it's inexpensive, will likely make the algorithm jump through (expensive) hoops to make the rest of the meal plan work - resulting in a net more expensive meal plan.

The "250 calorie" stipulation is arbitrary, and may be an issue for certain foods (looking at you spinach!), but it's a start.

...and something will need to be done for those foods that will demolish your nutrient scores even in low amounts (looking at you pickles, you sneak sodium monsters).

A Brief Aside...

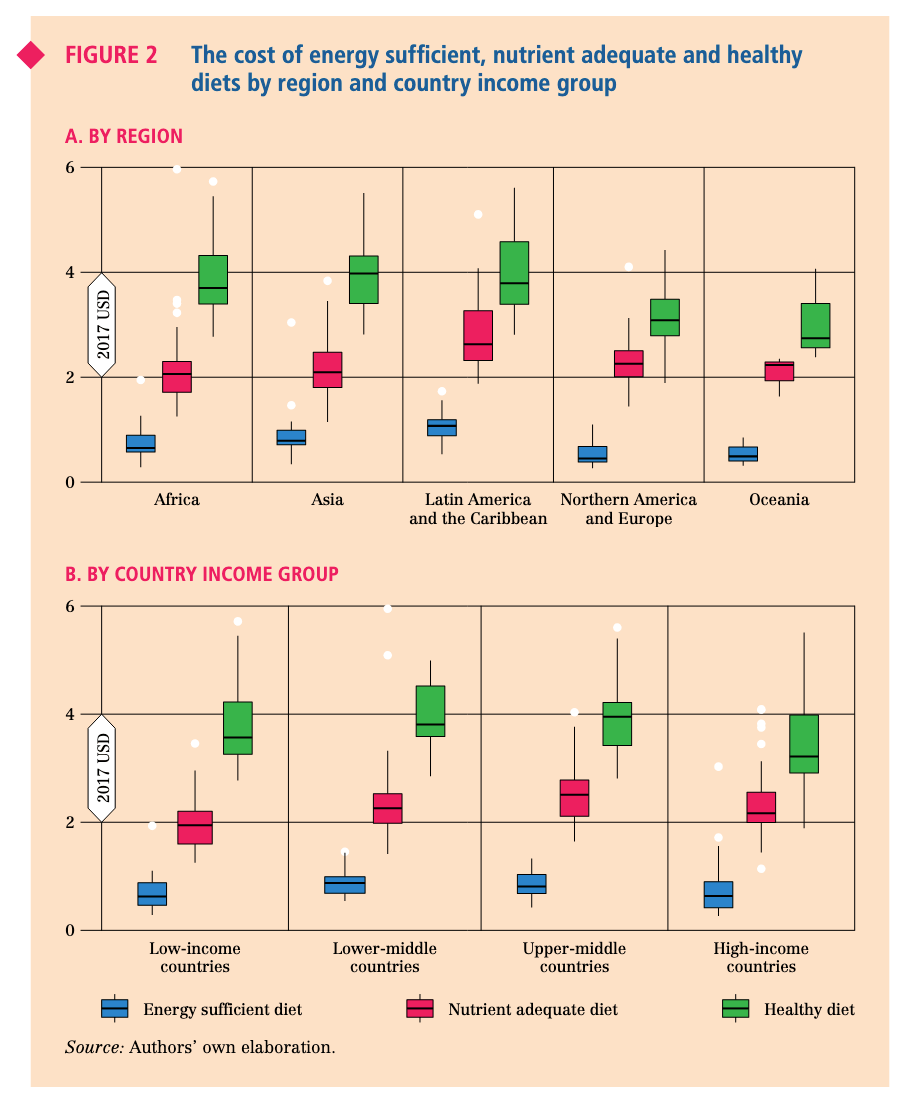

If you asked the average Canadian: "how much you have to spend each day to eat healthy?", I doubt you'd get an answer below $15/day. But based on the above it's probably possible for below $4/day. (The UN paper mentioned before certainly agrees.)

Speaking of dollars per day... if you had to guess, is it cheaper or more expensive to get food in a highly developed country (say, Canada) than a developing one (say, Tanzania)?

.

.

.

My thought was developed nations are more expensive, obviously. Everything is so much cheaper when traveling abroad.

But when normalized for price, food in developed nations is pretty much the same! (Again, from the UN paper)

Crucial note: given that Canadians earn many tens-of-dollars a day, while Tanzanians earn single digits, having the same baseline cost of food in those countries, even at "just" $4 per day, is a huge difference. For most Canadians "food" is solved. For Tanzanians, it's an existential challenge for people and logistical work-in-progress for their industry.

Bringing it all together...

So that's a lot of thoughts. And words.

Let's review and wrap up.

Eating healthy takes effort. Even in Canada, most people are not nutritionally informed and not well fed. The food industry has it's own interests, often not aligned with yours.

Broadly, I've been exploring this space because I want tools to help me...

- understand foods, their nutrition and their alternatives (to help me make long-term food choices)

- beyond spreadsheet, clustering groups of foods based on similar nutritional profiles

- and comparing with bougie score (v1 or v2)

- beyond spreadsheet, clustering groups of foods based on similar nutritional profiles

- understand what I'm missing (to fill in gaps, and change long term plans)

- meal evaluator (this meal plan is too high in sodium, too low in protein, ...)

- suggestions for alternatives (replace X with Y to save, or health)

- suggestions for gap-fillers (lacking folates this week, eat 150g of spinach)

- with in-the-moment decision aiding (make healthier or more financially rational choices in store)

- bougie scores

- alternatives and their prices

What does that look like?

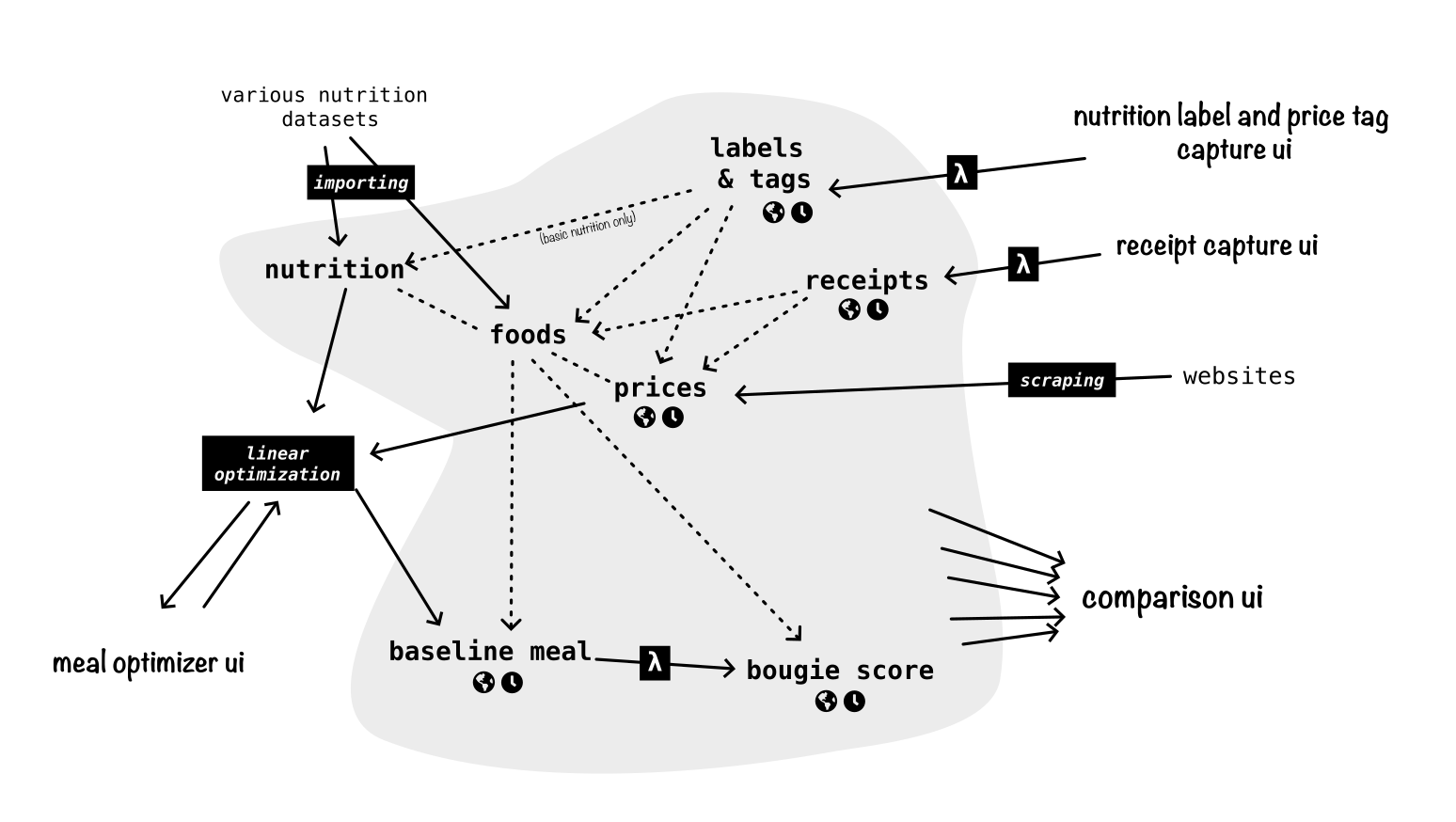

Above I mentioned several "parts" and I have several little projects. Brought together, they might look something like this:

That is: Getting food and price data from various sources (scraped, or crowdsourced). Organizing that data well. Integrating into a price-nutrition optimizer (and making that a whole user experience of itself). Calculating a baseline meal, for its own sake, but also to serve as a comparison to calculate a "bougie score" for foods (might need to change the name). ...and displaying all of this in a useful way, for planning/learning, and in the moment.

Next steps...

- better data

- via importing from external nutrition databases

- via scraping a few stores

- meal planner ui

- allow for "fill in the rest" optimization

- baseline meal calculation

- bougie scores calculation

- food comparison ui

- for a product

- bougie score v1 ( $ / 2kcal )

- bougie score v2 ( ?X of baseline )

- specific product price over time (at current location, and nearby)

- category similar alternatives (and their prices at current location and nearby)

- ex. "wonder bread" -> other breads

- nutritionally similar alternatives

- ex. "bread" -> rice, pasta, ...

- "high level recommendations"

- wait ("often on sale at this location - save $X")

- alternative brand / size ("instead of Premium Brand, Generic Brand - save $X")

- different location ("go to X store 250m away - save $X")

- alternative product ("instead of beef, soy beans - save $X")

- for a product

- in-store capture ui

- make it really quick and easy